I’ve got some new music coming out soon (more on that very soon!), but in the meantime I wanted to share this short piece I’ve written about a recent encounter in the woods. It’s called Waiting for the Nightjar - a short, dusk-time story about listening, birdsong and a fleeting moment I haven’t been able to forget.

I’ve also turned it into a YouTube video, so if you’d like to hear me read it and watch along, you can find that here.

Take care,

Alice

Waiting for the Nightjar

I’d heard there was a nightjar near these woods.

My partner had heard one the year before, and described the sound as “unusual” -“not like any birdsong he’d heard.” I stored the information in the back of my mind. Occasionally, the thought would find its way to the fore… I wonder what a nightjar sounds like. I wonder if I’ll ever hear one.

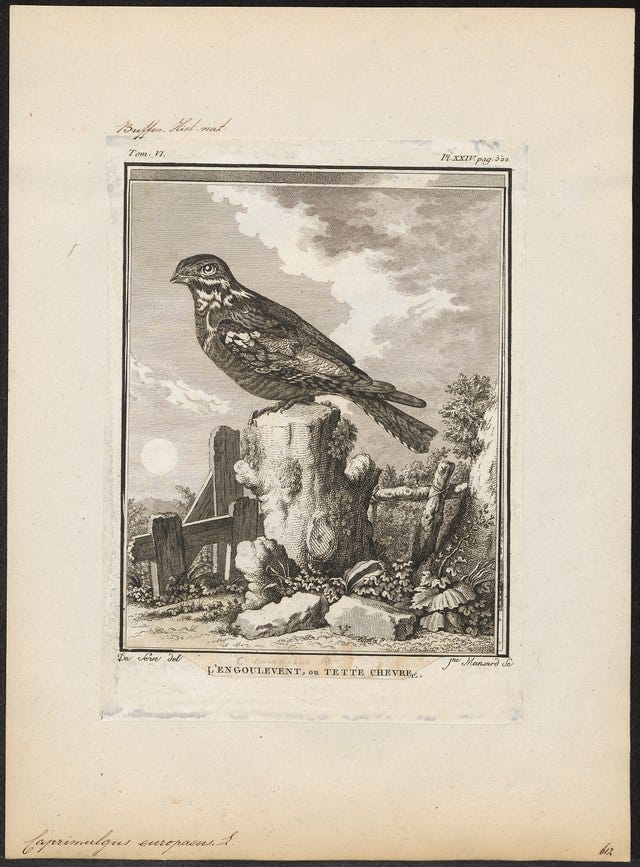

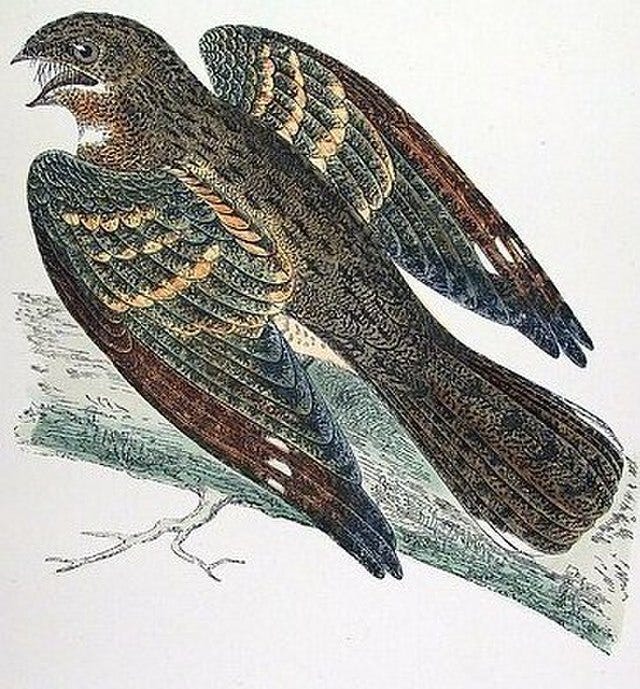

The nightjar is not a bird you’d hear in the day in your local park. The clue is in the name. They are nocturnal animals, preferring to call at dusk and dawn, hunting for moths and other flying insects in the near darkness.

In spring, they begin the long journey from sub-Saharan Africa, flying thousands of miles to nest in Europe. In the UK, they are most numerous in the south, but also find their way to Wales, northern England, and southwestern Scotland - where they stay until they leave once more for warmer weather in late summer and autumn.

There was only one thing for it: to set up camp in the woods and wait to see if I could hear the nightjar for myself.

While setting up the tent, I listened out for an unusual sound among the more familiar birdsong of the dusk chorus.

The second part of the nightjar’s name is inspired by its call: a jarring or churring sound.

Folklore has given them names like “fern owl,” “corpse bird,” and most strangely, “goat sucker” - a name going as far back as the 4th Century BC, when it was believed that nightjars drank the milk of goats, stealing the supper of the newborn kids. Their large mouths and proximity to livestock led people to believe this ancient myth. Now we know these adaptations are due to the bird’s appetite for insects.

As I was lighting the fire, I heard a strange noise - a mechanical whirring, almost purring sound, cutting through the rustle of leaves and hum of the distant road. Our ears pricked up. Could this be it?

Merlin ID at the ready, it became clear that this was indeed the nightjar. Cautiously and quietly, we headed further into the woods, growing closer to the sound, my field recorder in hand.

It’s close. In a nearby tree. I try not to get too confident, not to spook it. But it senses our presence and flies away. Shoot.

We pause, listening out for its call again.

And about twenty seconds later, we hear it - this time, in a tree deeper in the woods. We head towards it, aware that the bird senses our presence. And then the calling stops.

Out of nowhere, we see the nightjar swoop over the horizon. It flies up to us, spreads its wings - checking us out, or telling us to go away, that we are too close to its nest. We stand in awe. The nightjar calls out to its partner, who calls back - and then he flies off. We understand the message, turn around, and head back to our fire.

The image of the silhouetted nightjar spreading its wings sticks in my head. Only a metre or two away, its wings had looked like an angel’s. The moment felt charged, the light otherworldly as dusk fell, and the interaction heavy with meaning we could only try to decipher.

And although we didn’t hear the churring call for the rest of the evening, it remained lingering in the air as we told our friends of the encounter.

A few other things I’ve been working on…

Found Sounds - For May’s Found Sound of Ffern’s podcast As The Season Turns, I visited wildlife presenter, activist and birder Nadeem Perera. In this episode, Nadeem shares how birdwatching has changed his life, and his role in building community as co-founder of Flock Together. Listen here

Thank you to everyone who has listened to my new song ‘All We Are’. The track was inspired by the changing soundscapes of our natural world and shaped by my journey retracing the recordings of audio naturalist Martyn Stewart, nearly 50 years on. It’s a reflection on environmental change and the sense of “solastalgia” that can come with it. Listen here

A recent trip to Gloucestershire with writer Alice Vincent and filmmaker Camilla Greenwell took us to RSPB Highnam Woods, where we recorded some of the UK’s most endangered songbirds: nightingales. With only two males calling out for mates, it was a poignant reminder of what’s at stake. Listen here

Beautiful, so lovely to vicariously share this with you.